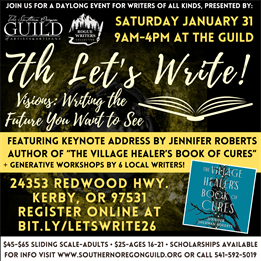

This keynote address was delivered at the “Let’s Write” conference put on by the Southern Oregon Guild of Artists and Artisans and the Rogue Writers Collective on January 31, 2026.

I was invited in part because of my activism in defending our local library from a termination of its lease. I was asked to talk about that experience and about my writing: I found that combining the two was a little more difficult than I anticipated. Hopefully I made it work (below). You can be the judge of that.

So, what do Shakespeare, Queen Elizabeth I, Josephine Community Libraries, Lin Manuel Miranda, Phillis Wheatley, Thomas Paine, Margaret Cavendish, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Octavia E. Butler, and Ursula K. Le Guin have in common? Read on to find out. (Spoiler: nothing, really, but they’re all in there!)

***

Given that the theme of this year’s writing conference is “Writing the Future You Want to See,” you may be wondering what an author of historical fiction has to offer you. I write about the past, after all, and not just any past—the extremely old and DUSTY past of the 16th and 17th centuries. And believe me, sometimes, when my eyeballs are burning from reading digitized copies of 17th-century handwritten recipes or pamphlets written during the English Civil War with titles like “Fire in the bush: the spirit burning, not consuming, but purging mankinde; Or, The great battell of God Almighty, between Michaell the Seed of Life, and the great red dragon . . . ” (I’ll stop there because it really does go on like that for a while)–that’s when I ask myself the same question: what does this have to do with my world today?

I don’t claim to speak for all historical novelists, but I imagine a fair number of us write about the past for two reasons: 1) it’s cool—I mean, the past is just COOL, sorry, can’t explain it better than that; and 2) we write about the past in order to make sense of our present and envision, perhaps even write into being, the future.

Those two reasons were my motivations for writing The Village Healer’s Book of Cures. I started researching recipes for an academic blog called The Recipes Project, which took medieval and renaissance household recipe books and analyzed the ingredients for medical recipes and recreated culinary recipes. I mean, that’s just objectively cool, right?

I was giving a talk about these recipes once for Oregon Humanities—I remember it was about a recipe for the Byte of a Mad Dogge (rabies) that called for crabapple that was harvested at night—and an audience member said, wow, that sounds so witchy! And the idea for the novel was born: a woman who used recipes passed down from her foremothers to heal her neighbors who is accused when a Witchfinder General comes to town.

E.L.Doctorow has said “The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.” In my novel, I wanted my reader to feel the yearning to learn and to understand the world that was felt by my main character, Mary–an opportunity to experiment and learn was an ambition denied most women at the time. I also wanted my readers to imagine what it must be like to be the victim of mob mentality in the witch hunts, to be accused wrongly in a society in which lives—of people, of animals—were often held cheaply.

Both The Village Healer’s Book of Cures and my next novel take place during the English Civil War, a battle over (among other things) the divine right of kings and the natural rights of the people.That sounds like such an ancient debate, doesn’t it, but think about it this way: I’m writing about a time when people are just trying to live their lives while surrounded by uncertainty and political upheaval, in an era of massive income disparity in which established political norms are going topsy turvy, and everybody is fighting over whether or not we should have a king. Like a nationwide No Kings Rally.

That all sounds pretty familiar, right?

I want my novels to be historically accurate but to speak to the times that we’re in. I want us to wonder: could it happen again? Could certain people, because of their identity, their religion, their interests, become scapegoats, targets of paranoia and hate in this modern world? What in the past has led to this happening and, by extension, what could we do–and how brave must we be–to prevent it happening again?

And I want to be clear that the desire to look to the past to explain the present is not modern.

For an example, we only need to look to William Shakespeare. In the series of history plays called the Henriad, for example (composed of the plays Richard II, Henry IV parts 1 and 2, and Henry V), Shakespeare traces the monarchy from the tyrannical Richard II—who has divided the kingdom, been abandoned by his allies, deposed, and murdered—to the triumphal Henry V, everybody’s friend Hal, who unites the kingdom, finds a French wife to promote peace with England’s enemy, and has a pivotal victory at Agincourt.

Shakespeare learned about the reigns of these monarchs from a book called Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, starting with events that happened about 200 years before his time. A contemporary example might be Lin Manuel Miranda reading Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton for inspiration for his broadway musical–after all, it was only 200 years ago that Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died (fun fact–they both died the same day–July 4).

Back let’s get back to Shakespeare, who borrowed from Holinshed and boldly reimagined—and in some cases invented from whole cloth—people, places and events in such a way that his audience could see not just the past, but a reflection of their own Elizabethan present.

As I said before, Shakespeare ends the Henriad with Henry V as a model of monarchy, a warrior-king: virile, likable, and quintessentially (according to Shakespeare’s plays) English. But that progression took time, and in order to show the stability of Henry V, a Lancastrian, Shakespeare had to show the tentative hold that Richard II, from the house of Plantagent, had on his crown.

At this point, I bet you all are thinking one of two things: either “Wow, this is like Game of Thrones! Amazing! Tell me more!”; or, more likely, you’re thinking “Ummm, I didn’t give up my Saturday to sit through a history lesson.” Fair enough.

My point—and I do have one—is this: Shakespeare didn’t consult Holinshed’s Chronicles to write his plays because he wanted to perform a flawlessly accurate view of the past. Indeed, he played fast and loose with the facts. No, Shakespeare used the past to explore what it means to live and believe in and just try to live your life in a monarchy. He used secondary characters, including the famous Falstaff and his tavern buddies, to show what it was like to live as a cog in the monarchy’s wheel, to have your fate determined by the whims of a king. In so doing, he held up the very idea of monarchy to the light, inviting his audience to think not about Richard II or the Henries, but about their current monarch: the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I. After all scholars believe Shakespeare wrote the Henriad in order to curry favor with Queen Elizabeth I, a descendant of Henry V, to shore up the strength of her claim to the throne.

But art is slippery, isn’t it?

People don’t always interpret things the way we hope they will. When the Earl of Essex commissioned a performance of Richard II to stir up the people before rebellion, Queen Elizabeth–without an heir and increasingly losing allies like Richard II–was suspicious. After Essex’s failed rebellion, Elizabeth is famously quoted as saying, “I am Richard II, know ye not that?”

It’s an object lesson to us all: we may think we’re writing a thing one way, but the readers can and will read it according to their own thoughts, fears, and ambitions. Soooooo, speaking of ambitious leaders who try to overturn the will of the people . . .

***

At the risk of giving us the bends after that deep dive into history, I’m going to bring us 400 years forward and back from 5,000 miles away, to our own Josephine Community Library.

As writers, I think it’s safe to assume that we all have a deep affection for libraries, and so many of you likely followed the kerfuffle between the Josephine County Board of Commissioners and Josephine Community Library District.

But here’s an overview, just in case: January 6, 2025, was the last day in office for Commissioner John West and the first day in office for Commissioners Barnett and Smith.

In the interest of full disclosure, one of the former commissioners has threatened to sue me for defamation for telling people this story, but everything I say can be verified through public record minutes, video, and newspaper stories.

So, on January 6, citing the need to “bring the library to the table,” the commissioners voted to terminate the library’s lease with thirty days’ notice.

The public was outraged and, with a mighty roar that involved protests and letters and phone calls, they let the commissioners know that the library was a precious community resource.

Voting to terminate the lease was bad. Very bad. But what followed was arguably worse: silence. For several months, there was no official action as a result of the vote. The library only learned of the vote because some dedicated volunteers who’d been watching a video of the meeting told them. A critical meeting was scheduled and then canceled at the very last minute. Quotes were given to media outlets but there was radio silence through official sources.

Finally, in May/June of 2025, Commissioner Barnett was chosen by the board as its official liaison, and he negotiated the lease with library director Kate Lasky. The two hammered out a lease that was agreeable to both parties. Because of what I can only describe as nonsense and tomfoolery from Commissioner Blech, it still took over two months for the lease to be signed.

As the co-chair of the Grants Pass Friends of the Library, it was my (volunteer) job to communicate with members about the state of negotiations. I was also interviewed by media outlets, and this meant countering a lot of faulty memories, gaslighting, and misinformation.

But what has this to do with writing and history, you ask?

Critically, this: the research habits I learned as a writer–tracking dates, quotations, statements, and votes–were invaluable, but even more important was the ability to use the details of what happened in the past to tell the story of what was happening in the present. My training and practice as a writer helped me navigate the consideration of audience and purpose, providing a framework for understanding, in context, what could otherwise be a jumbled pile of bureaucratic paperwork, contradicting statements, and yellowing scraps of newspaper stories.

Storytelling is not limited to writing a novel or a script. Sometimes it’s about the very survival of a beloved public icon.

***

While writing about the past can help us make meaning of the present, I also think our writing can help us imagine, evaluate, and perhaps even bring into being our future.

I’m reminded of a talk I went to by acclaimed scholar James Basker of the Gilder Lehrman Institute: Rhodes Scholar, Harvard and Oxford graduate and, interestingly enough, graduate of Grants Pass High. Several years ago, he visited the high school and gave a lecture to the seniors about two things: 1. applying to college, and 2. his own research into anti-slavery poetry of the Revolutionary Era. I yanked my daughter out of middle school (she was, and is, an avid history buff) and snuck into the PAC at Grants Pass High (don’t tell on me). In his talk, Dr. Basker argued that the poets of the Revolutionary Era–Phillis Wheatley, Thomas Paine, and others–were able, through their expansive imaginations, to write into existence the conditions that led to abolition. They may have written against slavery in their present, but their words created the world that could abolish slavery in the future.

When discussing futures and other worlds–any science fiction writers in here? Science fiction, to me, seems the natural home of imagining a future–whether utopian or dystopian. From my favorite relatively little-known woman writer of the 17th-century Margaret Cavendish writing about a “Blazing World” with animal scientists that talked; from Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who wrote the most sympathetic portrait of a monster I’ve ever read; to Octavia Butler, whose Parable of the Talents and Parable of the Sower are insightful to the point of prophetic.

And then there’s one of the great foremothers of science fiction: Ursula K. Le Guin who, incidentally, once visited Grants Pass library to do a talk with her friend (who was raised in Grants Pass), Roger Dorband. Le Guin wrote The Left Hand of Darkness in 1969, a book in which she famously created an ambisexual world that interrogated the idea of gender; and in The Dispossessed, she explored the tensions between capitalism and anarchy; individualism and community. Gender and social theory are hardly new themes, of course, but by releasing her imagination onto the page, she was able to usher in a world in which our very assumptions about society are held to a higher standard of thought.

The writer Julie Phillips wrote an article about Le Guin last year in Literary Hub called “The Way of Water: On the Quiet Power of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Activism, in which she highlights the most amazing quote. “In 1982, an interviewer . . . asked Le Guin what she would do to save the world. She answered impatiently: “The syntax implies a further clause beginning with if . . . What would I do to save the world if I were omnipotent? But I am not, so the question is trivial. What would I do to save the world if I were a middle-aged middle–class woman? Write novels and worry.”

For my next trick, if you can believe it, I’m going to come full circle and make 14th century and 16th-century England and a 21st-century globalized world meet. A few years before her passing, Le Guin won the prestigious National Book Foundation medal. At her acceptance speech in 2014, in a blistering defense of art over profit, she declared “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.”

And I think that’s what we writers do–we have the power and the responsibility to change things, to imagine other realities, to unleash our imaginations on the world. In doing so, we entertain, we comment, sometimes we convince–and at our best we always question. And worry. And act.

But above all–we write.