Happy Hallowe’en! During this time of unwitting mimicry of ancient ceremony and conjuration of forgotten powers, it seems only appropriate to venture into the world of Renaissance magic for this month’s “Peckie” (short for “Peckerhead,” of course).

***

Adopting an alias. Speaking with angels. Wife-swapping. If October’s “Renaissance Peckerhead of the Month” nominee Edward Kelley were alive today, he’d have his own show on TLC.

Edward Kelley is most famous for his partnership with John Dee, the great Renaissance magus and scholar. Dee served as an advisor to Queen Elizabeth, counted among his acquaintances Renaissance power mongers Frances Walsingham and William Cecil, and served as tutor to the poet Sir Philip Sidney.

In 1582, Kelley introduced himself to Dee. Dee had been increasingly obsessed with occult communication—specifically “angelic conversations” enabled by a scryer, one who could interpret the messages of a crystal ball. Kelley found Dee and gave him the happy news that his scryer-hunting days were over: Edward Kelley himself was just the man Dee was looking for.

Scrying was not, however, Kelley’s first career, nor was “Edward Kelley” his first name. Though Kelley proclaimed to have matriculated at Oxford, seventeenth-century historian of Oxford Anthony á Wood could find no student of that name during that time in any of the colleges of the university. He did, however, find a young man–same age, from the same place in Ireland–going by the name “Edward Talbot.” “Talbot” left Oxford abruptly–given that he was pilloried and had his ears clipped in Lancaster after that, as punishment for forgery, chances are he did not leave Oxford willingly.

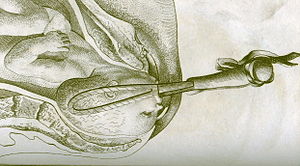

Kelley managed to convince Dee of his ability to speak with the angels. He described to Dee the process by which he received these angelic communications: He would see the celestial beings in crystal ball, and they would indicate letters on a tablet in their own language, a tongue Dee and Kelley called “Enochian.” English translations of the Enochian communications would unfurl from the angels’ mouths in paper ribbons. Dee seems to have been sincerely thrilled and amazed with Kelley’s astonishing ability to communicate with the angels.

Yup. Really.

Shortly after Kelley and Dee began working together, Kelley met and married the widow Jane Cooper, and, to his credit, seems to have treated her well, even arranging for her to have a Latin tutor.

In 1583, Dee, Kelley, and their families moved from England to Europe, trying to win the patronage of Emperor Rudolf II of Bohemia, himself highly interested in magic and alchemy. Having failed to secure his sponsorship, they traveled a bit before connecting with another patron, Vilem Rožmberk. They settled in the Bohemian town of Třeboň and began building a reputation for themselves.

Kelley was very, very good at building a reputation—in this particular iteration, it was as an alchemist, a much more lucrative trade than scrying. It was so much more lucrative, in fact, that Kelley began trying to get out of his partnership with John Dee. But how to do it?

Here’s where the movie of Edward Kelley’s life gets an “R” rating: scholars think that in order to convince Dee to sever their partnership, Kelley reported that an angel named Madimi ordered them to share everything they had—including Dee’s wife of nine years, Jane (Jane was 23 when she married the 51-year-old John Dee) and Kelley’s wife, conveniently also named Jane.

Dee wasn’t happy about the angel Madimi’s command, but on May 22, 1587, what Dee termed “the cross-matching” occurred. Nine months later, Jane Dee gave birth to a son, Theodorus Trebonius Dee.

After the “cross-matching,” Kelley left Dee in Třeboň. Dee went back to his home in Mortlake to find his library decimated and his collections ravaged. He died in poverty, forced to sell off various of his prized possessions.

Unlike Dee, Kelley went on to find fame, riches, and the patronage of Rožmberg; Emperor Rudolf II even had him knighted. Eventually, however, Kelley got caught in his web of deception. Rudolf had him imprisoned on a false charge of murder, hoping to keep him from leaving Bohemia with his “secret” for turning base metals into gold. Kelley died in prison in 1597.

Edward Kelley is considered the progenitor of the con-man-alchemist trope, the magician who fleeces his followers, as in Ben Jonson’s play The Alchemist. I imagine that in Disney movies and such he’d be the wheedling dealer in tricks, the man who betrays the good guy but really has a heart of gold.

Though something tells me if Edward Kelley had a heart of gold, he’d hock it.